.....................

Alexander the

Great

GUEST BLOGGER

War

History online presents this Guest Piece from Turin Bridge

Alexander

the Great is one of the most legendary kings of all time: in a ten-year period,

he conquered 90% of the known world, including the world superpower of his day,

Persia.

He

founded dozens of cities, was worshipped as a god, never lost a single battle

and began the process of cultural syncretism across much of Asia.

But

how did a relatively poor country such as Macedonia accomplish such incredible

exploits in a single decade?

What

made Alexander and his armies so incredibly invincible?

Phalanx

In simple terms, the Macedonian army was split between the

cavalry and the infantry.

Many

of the Macedonians’ enemies also had strong cavalry regiments – the Persians

recruited across many areas famous for horsemanship, such as Parthia and the

steppes on that count, but they could not stand against the Macedonian

infantry.

Alexander

infantry was arranged in a formation known as a phalanx, an evolution on the

earlier hoplite, who had fought so famously at Thermopylae and Plataea.

Much

like their Greek hoplite counterparts, phalangites fought using shields and

spears.

The

difference, however, was that the soldiers of the phalanx had their shields

strapped to take the weight around their shoulders, leaving both arms free.

This

meant they could wield a far longer spear, known as a sarissa–

a 21 foot-long spear.

In

battle, the men would be arranged in ranks sixteen deep, with the first five

ranks extending outwards and the ranks at the back tilting their spear to

deflect missiles.

Ultimately

this meant that in any given metre of the Macedonian line, there would

effectively be dozens of men fighting simultaneously.

This

made the phalanx a daunting unit for shock warfare, with maximum force being

brought to bear.

The

phalanx was well trained, it had to be strong to carry the long sarissa,

and was well-trained in drill.

During

Alexander’s campaigns, the phalanx was often used to hold and break enemies,

even if those enemies were highly equipped or fought in massive numbers.

For

example, at Guagamela, it was the phalanx that neutralised the Persian chariots

and kept Darius’s armies at bay for hours while the cavalry chased the King of

Kings from the field.

In

all of Alexander set-piece battles, the phalanx served as an inexorable anvil,

marching through their lightly armoured enemies, with none able to dodge

through the wall of spears.

Siege equipment

Alexander’s all-conquering army, like the

all-conquering army of Assyria before it, and the all-conquering armies of Rome

after it, had a dedicated corps of engineers who built and maintained siege

equipment, such as catapults, ballistae and siege towers.

This meant that enemies could not simply hide behind walls to

force a lengthy and costly siege.

The importance of this cannot be overstated; for most of his

early campaigns, Alexander was surrounded by wealthy client states of the

Persian empire who had access to the sea for supplies and only had to slow him

down in order for the Great King to rally his armies.

The ability to quickly reduce enemy strongholds quickly broke

the back of resistance in southern Anatolia and the Eastern Mediterranean and

may be why the satrapy of Egypt surrendered without resistance.

The siege corps came in use when reaching the far ends of his

empire.

When Alexander was at war with a tribe of Scythians in

modern-day Uzbekistan, he was confronted with a large army of mounted archers

guarding a river crossing and challenging his forces.

Alexander is recorded as using his missile throwers to

bombard the Scythians both before and as cover during the crossing – the first

instance of an artillery bombardment being used in this way in history.

Needless to say, the Scythians were dismayed at this display

of firepower and were promptly defeated once the Macedonians crossed the river.

The importance of

engineers is perhaps best demonstrated in Alexander’s most famous siege: at

Tyre.

Although the New

City was based on the mainland and was quickly occupied, the Old City was

located on a small island off the coast.

Tyre was part of a

confederation of Phoenician cities with strong navies who were strongly loyal

to Persia, and it resisted occupation by Alexander after he insisted on

sacrificing in their temple.

Being on an island

with plentiful food, supply lines, a strong navy, and allies, they trusted in

their walls and sea moat to hold off the invader until Darius could catch

Alexander on the coast.

It

is here that the value of the engineers quickly becomes apparent.

They

organised the destruction of the New City, for raw materials, and began to

build a solid rock path to link the island to the mainland that still exists to

this day.

Despite

heavy resistance, the Macedonians were able to mount towers on this stone

causeway that were taller than the walls.

They

were then also able to mount siege equipment onto ships (a marvel at the time)

and attack the city from all four sides, including the much lower, weaker

seaward walls.

The

conquest of such an invincible fortress, as well as others at Halicarnassus and

the Rock of Oxyartes had a far-reaching and profound effect on the people in

surrounding settlements: that resistance was futile, because they were no

invulnerable forts anymore.

Magnanimity

There were many times in which Alexander made examples of

his enemies, such as the slaughters at Thebes and Tyre, the destruction of

Halicarnassus and Persepolis, or dragging the Persian commander, Batis, around

the city of Gaza tied behind a chariot after that city’s fall.

However,

these examples stand out precisely because they are exceptions.

In

the main, most cities surrendered to Alexander willingly, and were treated with

great generosity and mercy.

This

policy, of punishing resisters and rewarding those who joined him gave great

dividends, for example, the wholesale surrender of Egypt, a jewel of the

Persian crown.

It is this policy

which is why Alexander was able to march straight from Guagamela to Babylon,

without resistance, march into the latter without a siege of any kind, resupply

and immediately continue the pursuit of Darius, preventing the Achaemenid King from

raising fresh armies in Iran.

It is fair to say

that with Alexander’s small army and limited initial resources protracted

resistance would have bled his forces white very quickly.

Alexander’s

open-handed treatment of those who came to serve him was the wise adoption of

the policy of Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Persian empire who had

conquered Asia himself roughly 200 years before.

As with Cyrus, it

allowed Alexander to rapidly expand his territory without having to parcel up

his forces into garrisons.

It meant that trade

was not interrupted by constant sieges, nor did he cause resentment by

punishing resisters with reprisals.

This goodwill

ultimately led to increased wealth towards his war efforts, as well as a large,

willing supply of manpower for his recruiters.

Alexander was able

to train regiments from across his empire; at the great review of his forces in

324BC, there were apparently 120,000 men in his army, including contingents

from Arachosia, Bactria, Sogdia, India, Scythia, and Egypt.

There was even a

company of all-Persian cavalry, made up of noblemen who served willingly.

It is hard to

imagine this being possible without the co-operation of his subjects.

Officers

As much of a genius as Alexander was, his conquests were

made possible because of the incredible work of his lieutenants and captains.

Alexander

was fortunate to inherit veteran commanders such as Parmenion, who held the

left at the Granicus, Issus and Guagamela, and Antipater, who acted as viceroy

in Europe, guarding against the Thracians and Spartans during Alexander’s

conquests in Asia.

As

his campaigns wore on, new men also emerged who helped make his vision

manifest, such as Hephaestion, Craterus and Perdiccas.

These

men would often be entrusted to lead sections of the army independently.

Here

a comparison between Hannibal and Alexander is important: whenever Hannibal’s

lieutenants were left to act independently, they would invariably be defeated by

the Romans, leading to Hannibal’s eventual defeat.

In

Alexander’s case, having men who could act on their own without supervision

allowed him to divide his forces for his lengthy guerrilla campaigns against

Spitamenes and Bessus in modern-day Afghanistan, leading to the Macedonian

victory.

This

trust in the competence of his subordinates is also very important for another

reason.

Signalling

an army was a difficult proposition in ancient times, which normally precluded

complex plans.

However,

since Alexander could rely on his officers to deliver results, it meant he

could enact advanced strategies to defeat his enemies. Nowhere is this better

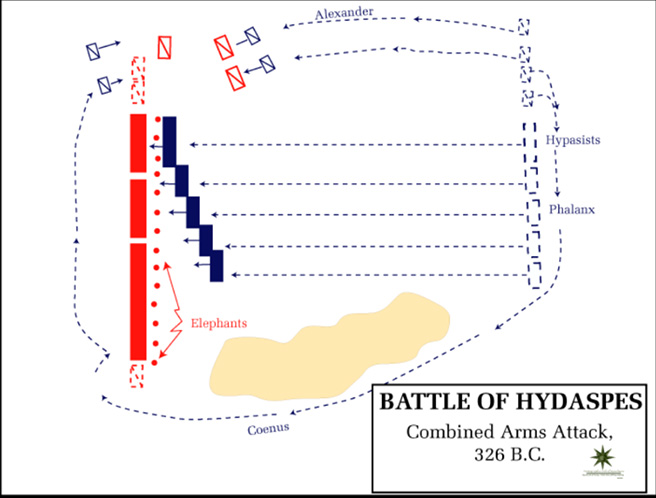

illustrated than at the Hydaspes.

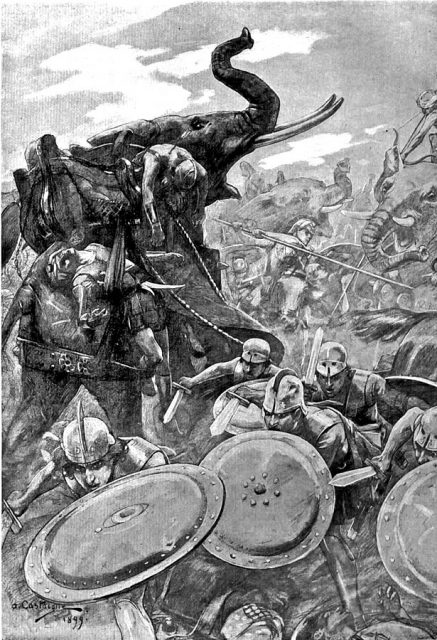

The forces of Alexander fought a battle at night, with units

speaking languages, in a battle which involved river crossings, during monsoon

season, to attack a well provisioned force with elephants and chariots, and

still won.

This incredible victory was brought about by the remarkable

work of the officers.

For example, Craterus had been left behind at the main camp,

to give the illusion of the presence of Alexander’s main force in order to

deceive the Indian king, Porus.

When Porus’ army turned to face Alexander, Craterus was able

to co-ordinate his own forces into another river crossing, which was then

flanking Porus.

Additionally, Coenus was able to launch a surprise attack on

the Indian right, throw it into disarray, before riding behind the Indian lines

and taking the Indian left in the rear, to co-ordinate with Alexander and

Hephaestion’s units, in what is one of history’s greatest cavalry manoeuvres.

Professionalism

Ultimately, Alexander’s army represented a truly

professional force, with an organised logistical corps, uniform equipment and

frequent drill.

Alexander’s

men could form many different formations very quickly and were well trained.

They

had been blooded while subduing the tribes of the Balkans and the Greek cities,

and were well versed in mountain and siege warfare.

Constant

drill also meant that soldiers could perform complex manoeuvres on a

trumpet-call and trusted the skills of the men around them.

Fighting

mostly militia and conscript armies in Europe and Asia, these professional

soldiers could trust in their abilities, compared to the poorly-equipped farmers

who faced them.

For example, at Chaeronea the Macedonian line staged a false

retreat, which deceived the levies of Athens into breaking formation.

On a trumpet-call the Macedonians uniformly turned face,

reformed, and then slaughtered this militia, destroying the Greek right flank.

This skill meant increased discipline, and bravery in the

face of diversity; when the lines were overrun during Guagamela, the phalanx

held firm until reinforcements were able to relieve them.

This

approach to army building not only led to creation of the engineer corps, as

described above, it led to the formation of a cadre of pages that allowed new

crops of officers to be raised, allowing the lessons of the past to be passed

on.

This

explains the rise of men such as Ptolemy and Seleucus, who had such incredible

careers during and after Alexander’s reign.

Comparable

to Sandhurst or West Point in modern times, it guaranteed the competency of

officers moving up the ranks, allowing for the level of independence and

co-ordination we saw at the Hydaspes.

Conclusion

Alexander was certainly a genius with the heroic bravery

that inspired his men to extraordinary heights again and again, however, we

should not ignore that his tools of conquest – his army was sublime.

Although

constantly outnumbered and often surrounded, Alexander was always able to bring

a local superiority of numbers; the one place at Issus

Alexander outnumbered Darius was where Alexander’s elite forces were directly

engaging the bodyguard of Darius himself, threatening the Persian king’s own

life.

Repeatedly

we see that Alexander’s greatest gift was his constant ability to have

numerical superiority at the most critical part of the battle: the enemy

general. This was only made possible through Alexander’s outstanding army.

As we can see using other remarkable generals as examples,

such as Hannibal or Belisarius, without the resources available to him,

Alexander may have never conquered anywhere near as much as he did.

Instead, he was able to quickly subdue his enemies, create

momentum and use that momentum to rapidly overwhelm his opponents, with minimal

attrition and establish the beginning of a new era that would last until the

rise of Rome.

No comments:

Post a Comment