.........................................................................

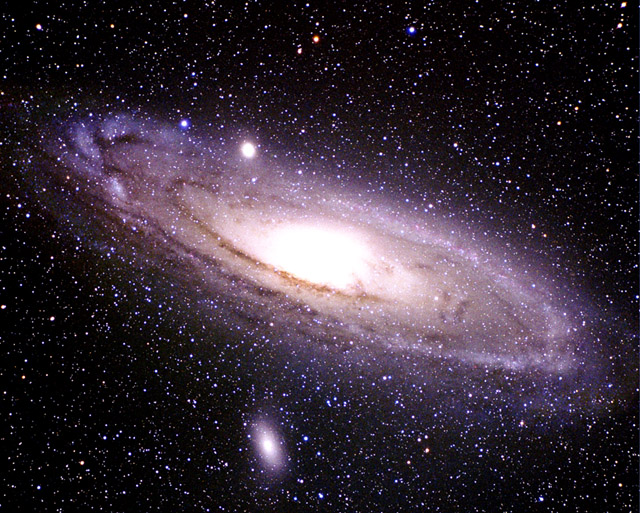

Life On Earth Is So Special

Is the Universe a Product of Design or Chance?

Is the Universe a Product of Design or Chance?

OPTIONS

FOR ORIGINS

The

choices in accounting for our universe boil down to three: Chance, multiple

universes, or design.

Scientists are looking at the extreme rarity of life in our

universe and asking, “why are we so

lucky?”

At some point you’ve got to step back from the facts and ask

the question “So what does all this

fine-tuning add up to?”

Example:

A

university student who’s just trying to get a passing grade might be satisfied

with loading

up his short-term memory with the data he’s received. But a student who is actually planning to use this information in a career, or for personal enrichment, has to spend some time thinking about the subject’s actual meaning.

up his short-term memory with the data he’s received. But a student who is actually planning to use this information in a career, or for personal enrichment, has to spend some time thinking about the subject’s actual meaning.

Same

thing with the question of how quasars, Pluto, and you got here.

The

evidences for the fine-tuning of the universe to permit life to exist on one

medium-sized planet, third from the left, are mounting.

Many

scientists are speaking in theological terms about what they see as clear

evidence for design.

If

you were to survey the writings of leading scientists such as Hawking, Penrose,

Davies, and Greene, you would find that there are three options being offered

for our origins.

• The fine-tuning of the universe is merely a coincidence.

• There are other universes, improving the odds of life.

• The universe has been designed.

LUCKY

YOU

Some

materialists attribute the fine-tuning of the universe to chance.

In Alpha & Omega, Charles Seife

summarizes how some view the fine-tuning: “It

seems like a tremendous coincidence that the universe is suitable for life.”

Cosmologists Bernard Carr and Sir Martin Rees state in the

journal Nature, “Nature does

exhibit remarkable coincidences and these do warrant some explanation.”

In a later article Carr comments, “One would have to conclude either that the features of the universe

invoked in support of the Anthropic Principle are only coincidences or that the

universe was indeed tailor-made for life. I will leave it to the theologians to

ascertain the identity of the tailor.”

In

other words, as a scientist, I don’t get into religion, so I

assume it was all a lucky break.

Scientists

who subscribe to a materialistic world view simply can’t bring themselves to

accept the intervention of an intelligent designer who orchestrated the creation

of the universe.

Therefore,

faced with all the evidence for fine-tuning, they default to the position that

it was all just a coincidence.

There

is, however, a defense often raised by those who take the viewpoint that life,

and the fine-tuning of the universe, are just amazing coincidences.

It

goes like this: Whatever shape the universe took, one could look at the

sequence of events and say that it was just as unlikely that the universe

should have developed in that way.

In

other words, every state of affairs, from a certain viewpoint, has astronomical

odds of its eventuating just the way it did.

So

why should we really be amazed that we won life’s cosmic lottery? Somebody had

to.

Let’s

consider how I lived out my day today as an example of this line of thinking:

What

are the odds that I would have gone to the post office, as opposed to the

grocery store or Blockbuster, and purchased 18 stamps instead of 20 or 30?

What

are the odds I would have received a phone call, rather than an e-mail, from my

friend Jeff?

What

are the odds I would have eaten — today of all days — hot dogs for dinner, when

I could have eaten so many other dishes that didn’t contain beef hearts?

By

the time you get to the end of the day, the odds of my living out my day in

exactly this way, as opposed to others, would be rather large.

I

could get to the end of the day and scratch my head in amazement at the chain

of events that have led me to my current sprawled position on my sofa staring

at my computer screen — Gee, what are the odds?

This

is a neat magic trick done with odds, and the inventor of it has a bright

career ahead of him as a pollster in politics.

Calculating

the odds for a particular sequence of ordinary events like my day’s

circumstances after they occur is no different

than predicting the winner of a race after it is over.

But

looking back on a finely-tuned universe and assigning probabilities of it

having occurred by chance is totally different. The two scenarios are different

as apples and oranges.

In

order to calculate the odds against our being here, over a hundred parameters

must be balanced on a razor’s edge. If just one of them was off by just a

slight degree, you wouldn’t be reading this.

ADD-ON

UNIVERSES

Most

scientists don’t believe such odds could be a coincidence. So how do

materialists explain odds that seem miraculous?

If

they don’t want to acknowledge an intentionally designed universe, they must

come up with another scenario that would explain it all, or their materialistic

premise is toast.

So

if you are trying to avoid the implication of a creator, you would want to

construct a theory that would decrease the odds of the universe being

miraculous.

If

you want to avoid the implication of a creator, your tack would be fairly

obvious: decrease the odds.

One

way you can decrease the odds is to add in the ingredient of several billion

years.

One

might imagine that the universe could plausibly bake up just about anything in

that much time, but even the 13.7 billion years that cosmologists estimate for

the age of the universe is way too short for life to have reasonably arisen by

natural means.

Therefore,

some scientists, such as Stephen Hawking and his Cambridge colleague Sir Martin

Rees, have taken a different approach.

They

have speculated that our universe might be merely one of many universes, thus

dramatically improving the odds for life in ours.

Let’s

listen to what Rees himself says concerning his motive behind the

multi-universe theory:

If one does not believe in providential design, but still

thinks the fine-tuning needs some explanation, there is another perspective — a

highly speculative one.… It is the one I prefer, however, even though in our

present state of knowledge any such preference can be no more than a

hunch.…There may be many “universes” of which ours is just one.

Rees

and Hawking have persuaded many in the scientific community that other

universes are possible, although highly speculative.

According

to Hawking, the multi-universe theory (also called the multiverse theory) would

rule out the need for a designer.

But

is the search for other universes driven by science, speculation or a

materialistic bias?

Seife, a mathematician and journalist for Science magazine,

explains what he believes to be the motivation behind the multi-universe

theory: “Scientists tend to be

uncomfortable with coincidences, and the many worlds interpretation gives a way

out.”

Rees,

a materialist, likes the multi-universe theory because it provides an

alternative to providential design.

The

undeniable reality of fine-tuning has energized the multi-universe theory,

since it gives hope to the materialist that life could exist without a

designer.

But

many scientists are raising their eyebrows at the speculative nature of the

multi-universe theory, considering its premise to be flawed.

IMAGINARY

TIME, IMAGINARY UNIVERSES?

Hawking

bases his theory on a mathematical concept called imaginary time, which is

merely a mathematical concept and doesn’t represent reality.

By

using imaginary time, Hawking is able to make it appear that the universe never

had a beginning.

Once again, scientists uncomfortable with a beginning are

seeking ways to avoid it. Hawking explains the reason for their avoidance: “So long as the universe had a beginning, we

could suppose it had a creator.”

Albert

Einstein used a different mathematical concept to remove the appearance of a

beginning. Later, Einstein admitted it to be his “biggest blunder.”

According

to theoretical physicist Julian Barbour, Hawking’s use of imaginary time may

also be a blunder. It has been “widely criticized” and has “technical

problems.”

Most

scientists are reluctant to endorse the concept of multiple universes because

it isn’t based upon any evidence, and can only be theorized in imaginary time.

Even

its greatest advocates, Hawking and Rees, admit multiple universes can never be

empirically verified. In The Elegant Universe, Brian Greene

calls the multi-universe theory “a huge if.”

Physicist

Paul Davies explains why materialists are so fervent in their attempts to

validate the multi-universe theory.

Whether

it is God, or man, who tosses the dice, turns out to depend on whether multiple

universes really exist or not. …

If

instead, the other universes are … ghost worlds, we must regard our existence

as a miracle of such improbability that it is scarcely credible.

Regarding

the multi-universe theory, Davies remarks, “Such a belief must rest on faith

rather than observation.”

Since

the multi-universe theory is based upon faith, most scientists regard it as

merely a hypothesis rather than a true scientific theory.

Yet

it still is being argued as a valid theory by Hawking, Rees, and others who

seek a materialistic explanation for our origin.

Investigative reporter Gregg Easterbrook, an investigative

reporter for the Atlantic Monthlyconcludes his research

on the multi-universe theory by stating: “The

multi-verse idea rests on assumptions that would be laughed out of town if they

came from a religious text.”

Hawking

and Rees should not be faulted for searching for a workable explanation; that’s

what scientists do.

But

this issue raises a red flag, not on Hawking or Rees, but (perhaps) on a

fundamental flaw of the scientific method.

If

it just happened to be true that God really was the cause of something, could

science ever discover this truth?

Wouldn’t

science have to offer a materialistic explanation, no matter how unlikely,

because the alternative is not an allowable option for them?

This

is, indeed, a problem, and it’s the issue that scientists who do see

intelligent design in the cosmos are wrestling with.

HANDMADE

UNIVERSE

In

Bringing Down the House, author Ben Mezrich tells the story of six MIT students

applying their skills in logic and mathematics to counting cards and other

trickery, who travel to Las Vegas and make millions.

They

were able to swing the odds in their favor. After a series of winning streaks,

they found themselves followed by house detectives who asked them to leave and

never return.

How

were they discovered? In one sense, they weren’t. No one actually ever caught

them cheating, but the MIT students did do something that was a dead giveaway:

they won.

Repeatedly

they beat the odds, and when the dealers and house detectives in Las Vegas

observe someone repeatedly beating the odds, they suspect intelligent design:

someone is not playing by the laws of random chance but by a carefully reasoned

system, like card counting.

The

fine-tuning in the universe is astounding and unimaginably improbable.

It

could be all coincidence or chance, or maybe there are multiple universes,

raising the odds and probability of life, but a good detective would be wise to

consider the distinct possibility that intelligent design lies behind the

observable phenomena.

TO

HUME IT MAY CONCERN…

It

is primarily due to the arguments of 18th-century English philosopher David

Hume that science has largely dismissed any argument for design in the

universe.

As a

materialist, Hume argued that the universe was a result of chance rather than

of intentional design. He believed miracles were impossible because they

couldn’t be subjected to scientific verification.

Hume’s

arguments refuting intelligent design have been extremely effective in

persuading scientists that all events in the world are from chance alone.

Hume’s basic logic is as follows:

1. The world is ordered.

2. This is due to either chance or design.

3. It is very possible that the world came about by chance.

Hume had several other arguments against design, but

according to mathematician William Dembski, he used faulty logic. “Hume incorrectly analyzed the logic of

the design argument, for the design argument is, properly speaking, neither an

argument from analogy nor an argument from induction but an inference to the

best explanation.”

Although

Hume’s influence on science has been pervasive, he lived in a day when

astronomy was in its infancy and the prevalent theory favored an eternal

universe. He wasn’t aware of the big bang theory that points to a beginner, or

the design implications of fine-tuning.

The

recently discovered fine-tuning of the cosmos has compelled even the most

ardent materialists to consider the possibility of intelligent design. What is

the best explanation for the fine-tuning?

When Hawking first realized that the universe couldn’t be a

mere coincidence, he related to a reporter, “The

odds against a universe like ours emerging out of something like a big bang,

are enormous. … I think clearly there are religious implications whenever you

start to discuss the origins of the universe.”

Davies concurs. “It

seems as though somebody has fine-tuned nature’s numbers to make the Universe.

… The impression of design is overwhelming.”

Some

scientists, such as Hawking, are uncomfortable with the obvious religious

implications.

But

cosmologist Edward Harrison speaks for others who respond to the evidence for

the fine-tuning by clearly stating the obvious:

“Here is the cosmological proof of the existence of God. …

The fine-tuning of the universe provides prima facie evidence of deistic

design.”

Take

your choice: blind chance that requires multitudes of universes or design that

requires only one.

Many

scientists, when they admit their views, incline toward the … design argument.

Few

scientists believe the precise fine-tuning is merely a coincidence. While some

hold to the multi-universe theory, most scientists believe such a speculative

theory is beyond the boundaries of science.

Many

credible scientists have been persuaded by the evidence that our universe is

not here by accident but rather is the intentional plan of a super-intelligent

being.

Dr.

Robert Jastrow is a theoretical physicist who joined NASA when it was formed in

1958. Jastrow helped establish the scientific goals for the exploration of the

moon during the Apollo lunar landings.

He

set up and directed NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, which conducts

research in astronomy and planetary science. Jastrow wrote these thoughts that

summarize the view of many scientists.

For

the scientist who has lived by his faith in the power of reason, the story ends

like a bad dream.

He

has scaled the mountains of ignorance; he is about to conquer the highest peak;

as he pulls himself over the final rock, he is greeted by a band of theologians

who have been sitting there for centuries.

THE

ANTHROPIC PRINCIPLE

Astrophysicist

Stephen Hawking cites the term “anthropic principle” when attempting to explain

why the universe is so exquisitely fine-tuned for life.

Hawking writes, “it

seems clear that there are relatively few ranges of values for the number that

would allow the development of any form of intelligent life. …One can take this

either as evidence of a divine purpose in Creation and the choice of the laws

of science or as support for the strong anthropic principle.”

Hawking

has advocated the strong anthropic principle solution of many universes in

order to avoid the conclusion of a designer.

The

anthropic principle is a fancy term for stating the obvious about the

fine-tuning of the universe, i.e., if all the conditions in the universe

weren’t perfect for human life to exist, we wouldn’t be here to ask the

question of why it is so finely-tuned for life.

What

sounds like circular reasoning has led to a revival of the argument from

design, which had lost its intellectual respectability among many scientists

after Darwin.

One

aspect of the anthropic principle is that it asserts that our place in the

universe is special.

This

contradicts the general trend of science since Copernicus; that there is

nothing special about Earth (the Copernican principle).

Many

materialists who dislike the implications, squirm when discussing the anthropic

principle, and it remains a controversial topic.

But

thus far, no scientist has been able to refute the fine-tuning evidence that

supports its premise, and many believe it is simply a commonsensical way of

saying life on Earth is special.

No comments:

Post a Comment