|

| Two Yaohnanen tribesmens show framed pictures of their 2007 visit with Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. |

Cargo Cults

On

One Pacific Island, a U.S. Soldier and Prince Philip Are Gods

On

One Pacific Island, a U.S. Soldier and Prince Philip Are Gods

In Vanuatu, a South Pacific island nation that's a three-hour or so flight east-northeast of Sydney, Australia, the mystic figure known as John Frum is alive.

Well,

as much as he's ever been

alive. He is not alone. John Frums, some will argue, "live" all over

the world. Even in places you wouldn't expect.

On

the tiny island of Tanna in the Vanuatu archipelago — overall population about

250,000 — a vocal lot of locals still worship John Frum, a mythical personage

often depicted as a white American World War II soldier (though he has been

described in different ways).

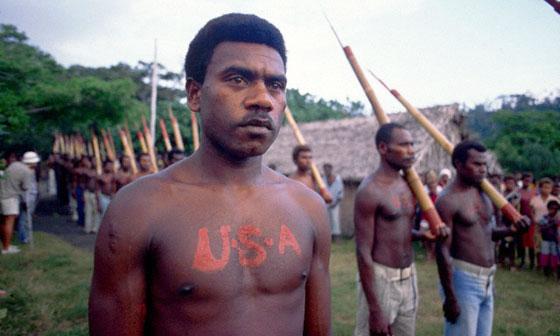

Every

year on Feb. 15, Frum followers celebrate John Frum Day.

They

raise the U.S. flag. They march in formation with rifles made of bamboo. Older

islanders dress in military outfits, complete with medals.

Years

ago, they carved airstrips out of the jungle, complete with fake planes.

They

honor John Frum and prepare for his return and the good times — and material

things —that will come with it.

All

this, it should be noted, for someone that outsiders believe sprung from the

minds of elders high on kava, a local plant with slightly psychoactive

properties.

Frum

followers are leading examples of what many anthropologists label a "cargo

cult," which is in itself a kind of moving target of a term that

scientists now struggle to accept.

The

term has been used largely for groups in the Pacific, those in less-developed

societies conducting what are seemingly strange and primitive rituals.

The

label is still used, but not as much. Calling something a "cult,"

after all, is a tad pejorative. Even the word "cargo" may not

represent what it once did.

However

the groups are tagged, they persist, some to the point that they have become

legitimized parts of society. And they're not all relegated to the jungles of

faraway islands.

"It's

not just something that's in Vanuatu or New Caledonia or New Guinea. It's not

just the 'primitive' spots,"

says John Edward Terrell, the Regenstein Curator of Pacific Anthropology at

the Field Museum in Chicago. "That's

why I argue that Trumpism is a 'cargo cult.' It's right here at home."

The

Granddaddy of Cargo Cults

The term "cargo cult"

originated in 1945 with the John Frum movement, which began in the early part

of the 20th century.

The

Frum movement gained followers during and after World War II when islanders,

seeing cargoes of food and goods that American soldiers brought, went full-in

(probably after a night of sipping kava drinks) on the idea that an American

savior would reappear after the war, bringing gifts of "cargo."

"John

promised he'll bring planeloads and shiploads of cargo to us from America if we

pray to him," a village elder told Smithsonian

Magazine in 2006. "Radios, TVs,

trucks, boats, watches, iceboxes, medicine, Coca-Cola and many other wonderful

things."

More

than cargo, though — and one reason that anthropologists avoid using the term

"cargo cult" - the promise of John Frum then, and now, is to throw

off the yoke of colonials who for years pushed strange religions and

customs on a people rich with their own history and kastom.

The followers of Frum at one time were told by their

leaders (who, ostensibly, heard from John himself ... again with the kava) to

stop listening to the missionaries and to "drink

kava, worship the magic stones and perform our ritual dances,"

according to what a village leader told Smithsonian.

That

desire for more than just cargo — for a better, more authentic life — has paid

dividends on the island, even as worshippers await the return of their man. The

John Frum Party is now represented in the Vanuatu parliament.

The

Frum movement is not the only "cargo cult" still active in the

Pacific.

Also

on Tanna, a small sect worships the United Kingdom’s Prince Philip, believing

the Duke of Edinburgh (and husband to Queen Elizabeth II) is a divine being.

Several

other groups have been ID'd as "cargo cults" in Papua New Guinea and

elsewhere.

"It

is a social phenomenon; you have to be able to, in a sense, tell it to other

people," Terrell says. "People can connect with the idea that,

'It's all going to get better if we do X or Y.'"

What Cargo Cultists Want

These "revitalization

movements," as famed anthropologist Anthony F.C. Wallace more

tastefully called them, are no different than what many cultures throughout the

world experience throughout history.

The

people in these crusades want what we all do — a better life.

Wallace

spelled out five phases in the development of these movements; Terrell has

boiled them down here, from the point of view of those experiencing it. (We've

shrunk them even more.)

1. Once,

life was good. We were happy.

2. Things

got worse, and we got a little less happy and more restless.

3. It

got really bad, and we started looking for ways to make things better.

"Disillusionment and apathy became common."

4. Somebody

with what Wallace called a "vision dream" — gained in any number of

ways, tangible or intangible, of this world or beyond it — suggested a better

way. Converts were made. More people, seeking a better life, joined in. A

movement was born.

5. The

movement lives until the dream is realized or dashed.

How Cargo Cults Relate to Today's

World

The idea of people wanting to

improve their lot, and waiting on someone to help them do it, should not be,

Terrell suggests, some strange concept.

Entire

religions — not just John Frum — are based on it. Whole societies turn on it.

Unhappy?

Looking for more meaning in your life? Want to return to a happier time? A,

shall we say, "greater" time?

Donald

Trump, anyone? Brexit, perhaps? The Arab Spring? Russia under Putin?

It

turns out that the "cargo cults" of Vanuatu aren't all that different

from the rest of the world when it comes to what they want.

"I

don't think it always has to be about 'How it had been was much better, and if

we can only get back, we'll all be fine,'" Terrell says. "But

Trumpism clearly does [that]. I don't think it's any exaggeration that Trumpism

has all the earmarks of a cargo cult. It's about the power of belief. And the

power of persuasion."

NOW THAT'S INTERESTING

Anthropologist Lamont Lindstrom explains the early

labeling of "cargo cults" this way: "Any sort of woeful or forlorn desire for material goods or other

coveted objective, joined with a seemingly irrational program to obtain this,

can be blasted as a wrongheaded cargo cult."

Anthropologist Lamont Lindstrom explains the early

labeling of "cargo cults" this way: "Any sort of woeful or forlorn desire for material goods or other

coveted objective, joined with a seemingly irrational program to obtain this,

can be blasted as a wrongheaded cargo cult."

Whether

it's stories about John Frum followers in Vanuatu or Trump followers in Iowa,

Lindstrom says, they all rest on this basic human trait. "Cargo stories are desire stories. They function to remind us how

modern, consumerist desire operates. This is desire — for things as for others

— that is never sated."

John Donovan

CONTRIBUTING

WRITER

John is a

freelance writer based in the suburbs of Atlanta. A longtime sports scribe with

too much time covering college sports, the NFL, the NBA and Major League

Baseball, he now writes on science, health, history, current events and

whatever other weird non-sports stories that he and the editors at

HowStuffWorks dream up. He has a journalism degree from Arizona State, a wife,

a son, a dog that sheds too much and a bad case of eyestrain.

No comments:

Post a Comment